More fun with visualization: word clouds

I’ve been slowly and steadily adding to the Potential Book Project database that I wrote about in the previous post, and somewhat to my shock, I realized that I’ve now got entries for over 1500 individual poetry quotations from 24 commonplace books compiled between 1800 and 1900. (And I’m still nowhere near done; I’ve got many more notes from various research trips made over the past several years.) There’s going to be a ton of data when I’m done. But I’m starting to think that, yes, there’s already enough data for me to start making some generalizations, and really there could be at least a couple of articles in all of this right now. And there are a lot more ways I can experiment with visualizing some of that data to clarify my thinking about it.

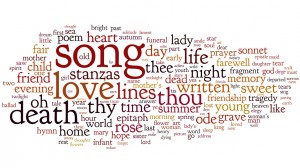

Today it occurred to me, as I eyeballed the “poems” table in the database, that maybe the titles of the poems could tell me something.* On a whim, I copied the entire column of titles and pasted it into Wordle. I’m not always a huge fan of word clouds; sometimes they don’t tell you much that you don’t already know. But the word cloud I got out of the title list is actually interesting, because it adds some weight to an impression I’ve been getting all along, namely that commonplace books were the great repositories of sentimental verse:

Some of the most prominent words are the obvious ones that appear in poem titles, like “song,” “sonnet,” “ode,” or “stanzas.” But the elegiac nature of a lot of the poems in these collections becomes evident when you notice the prominence of “death” and related words: “dead,” “funeral,” “grave,” and “epitaph.” Equally prominent are the relationship words: “mother,” “child,” “infant,” “friend,” “friendship,” “sister,” “daughter,” “love.” (“Memory,” I’d argue, encompasses both.) Looking at this visualization, you start to realize just how many poems are about either the bonds between family, friends, and lovers, or the death of a loved one, or both (frequently both, in the case of the innumerable poems I’ve found about grief over the death of children).

In “Reclaiming Sentimental Literature,” Joanne Dobson reads sentimental nineteenth-century American writing as foregrounding the interconnections between people:

Sentimentalism envisions the self-in-relation; family (not necessarily in the conventional biological sense), intimacy, community, and social responsibility are its primary relational modes. This valorization of affectional connection and commitment is the generative core of sentimental experience as mid-nineteenth-century American writers defined it.**

I have a theory that the same set of attitudes informed not just my compilers’ choice of poems, but in many cases the contexts in which they chose them (groups of school friends taking turns filling books with poems to remember each other by; family members passing their collections down as mementos). It’s nice to see that laid out as obviously as this word cloud does.

* This was perhaps cheating a bit, as there are a number of first lines in the title list, given the need to distinguish similarly titled poems and the tendency of poets to call their poems “Stanzas.” Or “Song.” Or “Lines.” It would probably be even more informative to do a word cloud with the full text of all the poems, but I don’t have that, because finding and scraping and cleaning up the text of every individual poem would take another few years all by itself.

** Joanne Dobson, “Reclaiming Sentimental Literature,” American Literature 69 no. 2 (1997), 267.

Comments are closed.